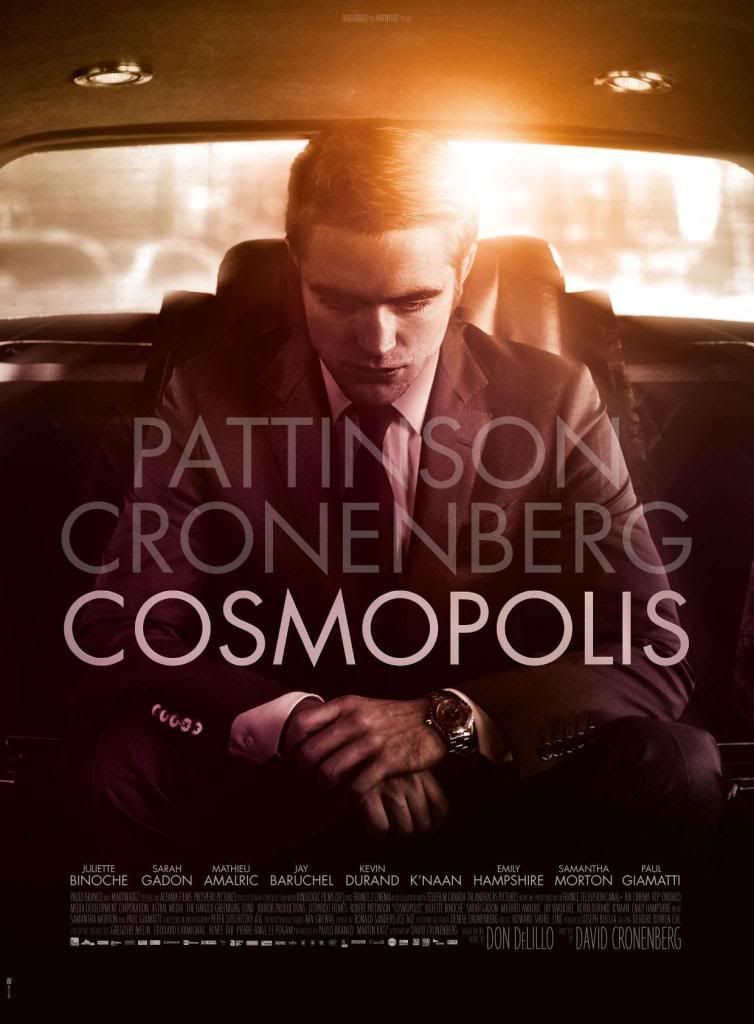

"Cosmopolis" Review by Little White Lies

David Cronenberg’s superb latest is an existential road movie for our

financially and morally bankrupt times, interested as much in addressing

the semantic minutiae of the corporate apocalypse as it is deep felt

anxieties relating to stress, success, control and our inability ward

off death with money and status.

Like The Social Network, it combines a credible depiction of a person

whose age and intellect are dangerously off kilter, while sending its

‘hero’ on an anti-capitalist nightmare odyssey that discharges all the

dry cynicism and insouciant doomsaying of Godard’s Week End.

Very neatly abridged by Cronenberg himself from the 2003 novel by

American postmodernist writer, Don DeLillo, his screenplay filets out

much of the dialogue from the source while expunging the flashbacks,

dreams and internal monologues.

Robert Pattinson is magnetic as Eric Packer, slick, jaded 26-year-old

CEO of Packer Capital who decides to take a fleet of Limousines across

across New York City in search of a haircut. This is his best

performance to date by some considerable margin. Yes, even better than

Remember Me.

But there’s something strange about this idle whim. Eric is a man to

whom people and services come, not the other way around. As his loyal

security guard, Torval (Kevin Durand), says, he could have a barber come

to the office, or even to the Limo. During a single day, Eric

experiences an Icarus-like fall from grace while numerous acolytes and

paramours visit him in his cab to chat numbers, health and even the

sudden death of rap megastar, Brutha Fez.

People want Eric dead, or in the case of Mathieu Amalric’s mad Andre

Petrescu, to throw a pie in his face. He has become a walking wanted

poster for the corporate scourge who cheerfully wipe out millions with a

few swipes of touchscreen computer. For Eric, murder is also starting

to shed its taboo status.

It’s a richly verbose film, even more so than his majestic, 2011

exploration of extreme emotional repression, A Dangerous Method. It gets

to the point where much of what is spoken cannot be fathomed – “talent

is more erotic when it’s wasted” – but the film is about the rhythms of

dialogue, the verbal posturing, sparring and deceptions employed in the

economic sector.

The way in which Cronenberg photographs the talk, too, is subtle,

elegant and intense without ever drawing undue attention to itself or

feeling overly oppressive. Per Cronenberg himself, this is a film in

which “fantastic faces say fantastic words”.

Beyond its withering critique of contemporary capitalism, Cosmopolis is

also fascinated by that ongoing Cronenbergian concern: the limitations

and mutations of the human body. Eric desperately wants to scale an

economic Mount Olympus and be able predict the permutations of the

Chinese Yuan, and his inability to attain this level of cerebral

perfection acts as a signifier for his mental and physical decline.

In one scene, Eric has a prolonged rectal examination after which he is

informed that his prostate is asymmetrical. In a climactic showdown with

a disgruntled, pistol-wielding ex-employee (Paul Giamatti), this small

bodily imperfection becomes the key to understanding Eric’s meltdown.

This film clocks up the astronomical price of achieving so much at such a

young age, when your body and mind reach a state where there is no

reason left for them to function.

"Cosmopolis" Review by Empire

Somehow David Cronenberg's Cosmopolis articulates everything I think

about post-financial crisis capitalism, ie, the world today. It goes

without saying that it is weird, but even from the director of eXistenZ

and Videodrome it is bizarre, with the mannered, affected performances

of the former and the outsider characters of the latter. It doesn't

quite fit with the early body-horror movies but there is, like A

Dangerous Method, a viral metaphor at play here, and this time the virus

is not free thought but the free economy (towards the end of the movie,

Robert Pattinson's vampiric playboy comments that “nobody hates the

rich, everybody thinks they're ten seconds away from being rich”). But

what is money? Is it the dollar? The baht? The dong? Could it be a rat? A

live rat, a pregnant rat or a dead rat? What does money even mean?

Cronenberg's cool, intelligent film asks all these questions – literally

– and more, then goes even further, asking: what does meaning mean?

Seriously. Even by the director's lofty standards this is a talky film,

and most of it goes round in circles. As promised, it concerns a limo

ride to get a haircut, but Cosmopolis – based (to what extent I have yet

to find out) on Don DeLillo's novel – is a surprisingly roomy affair,

and not simply a one-set gimmick. In some senses it resembles Godard's

Weekend, since the traffic is terrible and civilisation seems to be

crumbling outside it, but this will also play well to genre fans and is

definitely one of Cronenberg's most ambitious movies to date.

For Robert Pattinson, however, this is another league, and his celebrity

status certainly suits the part. He plays Eric Packer, son of a

super-rich businessman, a society kid who has made his fortune with

mysterious dotcoms and by playing the money markets. Today he is betting

against the baht and losing hundreds of millions of dollars in the

process. The inside of the limo glows with LED screens, and Eric is

joined by a roundelay of guest stars (including a very slinky Juliette

Binoche and, more surprisingly, an edgy Samantha Morton) who engage him

in bizarre, solipsistic conversations. These talks border on self-parody

but somehow they work. It reminded me of Roy Andersson's wonderful

Songs From The Second Floor, since this is what the end of the world

probably would sound like. Though the budget is clearly quite low,

Cronenberg does convincingly convey a sense of apocalyptic doom, from

his characters' psychotic babble (at one point Eric is attacked by the

custard-pie wielding Pastry Assassin) to a full-on riot that covers the

pristine car in spraypaint and anti-capitalist graffiti.

The stylised nature of the language will limit this film's appeal, and

its self-conscious craziness might also be testing to some (why does the

professional barber Eric finally visits cut huge steps in his hair?).

And after Water For Elephants it remains to be seen whether Pattinson's

teen following really is willing to follow him anywhere. But Cosmopolis

does prove that he has the chops, and he parlays his cult persona

beautifully into the spoiled, demanding Packer, a man so controlling and

ruthless that only he has the power to ruin himself. Lean and spiky –

with his clean white shirt he resembles a groomed Sid Vicious –

Pattinson nails a difficult part almost perfectly, recalling those great

words of advice from West Side Story: You wanna live in this crazy

world? Play it cool.

"Cosmopolis" Review by the Playlist

"Cosmopolis," an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s typically provocative novel

of the same name, is the first feature film since 1999's "eXistenZ"

that filmmaker David Cronenberg has directed and scripted. This in part

explains why "Cosmopolis" is such a triumph: it’s both an exceptional

adaptation and a remarkable work unto itself.

Cronenberg makes slight but salient changes to DeLillo’s source

narrative. These changes, which are best described by one character as

“slight variation[s],” prove that Cronenberg’s given serious

consideration to what should and shouldn’t be represented in his

adaptation of the author’s ruminative, conversation-driven narrative.

For example, in Cronenberg’s film, Eric Packer (a surprisingly adequate

Robert Pattinson), an ambivalent and self-destructive power broker, does

not get to have sex with his wife like he’s wanted to do throughout

DeLillo’s book. Other changes, like the fact that Packer is investing

and studying the steady rise in the Chinese yuan in the film and not the

Japanese yen, as in the book, are equally striking. These differences

noticeably enrich DeLillo’s original story, making Cronenberg’s

"Cosmopolis" that much more rewarding in its own dizzying way.

It’s fitting that Pattinson, today’s It boy, plays Packer, considering

who Cronenberg’s Packer is. As a former start-up wunderkind, the 28

year-old Packer is comically death-obsessed. “We die every day,” he

risibly exclaims to one of his sizeable retinue of advisors. Packer gets

daily check-ups from his doctors partly because he enjoys the routine

of it but also because he’s looking for something to confirm his

suspicions. He’s convinced he’s found that something when he’s told that

his prostate is asymmetrical. It’s pretty funny to see Pattinson, being

the young, pretty tabula rasa that he is, play Packer, a wheeler-dealer

that used to be hot shit but is now unable to sleep because he fears

that he’s no longer relevant.

Throughout both versions of "Cosmopolis," Packer searches for a break in

his routine. Against the advice of his over-protective bodyguard Torval

(Kevin Durand), he fights back anarcho-protestors and gridlock traffic

caused by the President’s visit to another part of town, so he can go

get a haircut. The ritual, and also the familiarity of this ritual, is

what matters to Packer. But Packer also insists on going out and getting

his haircut now because, as he explains during one of many declamatory

speeches, of the turbulent conditions Torval has warned of. He’s no

longer waiting on his death, he’s inviting it.

Packer is in that sense, as is also later explained point-blank in a

speech, a contradictory figure. For example, he allows Vija Kinski

(Samantha Morton), one of the more decisively outspoken of his advisors,

to tell him that the anti-capitalist protestors that are impeding his

progress are actually just another part of the capitalist system.

Pattinson’s Packer latently agrees with this assessment but that changes

when he sees one protestor self-immolate himself. Kinski insists that

the protestor’s gesture is unimportant, but Pattinson sulkily protests

that it has to be. The fact that Pattinson’s practically pouting when he

rejects Morton’s negative assessment is telling. His death wish is

sheer petulance, something that doesn’t come across as directly in the

original novel.

Cronenberg and Pattinson’s Packer is a different kind of suicidal but

their character isn’t significantly less active in constructing his own

demise. In DeLillo’s "Cosmopolis," Packer knows what’s happening with

the yen, whose value keeps exponentially increasing, but is keeping that

knowledge close to his chest. In Cronenberg’s variation, Packer is less

sure. Pattinson’s Packer is thus more immediately defined by his

frustration with the finite-ness of his capabilities. He looks to others

for solutions to his problems and finds that his yes-team can only

confirm his own impotence. The film version of Packer is not slyly

organizing his own downfall, he’s frantically seeking it out, unsure of

whether or not he can find what he’s looking. Pattinson’s Packer only

succeeds by sheer dumb luck: an assassin is looking for him and he and

Packer have a lot more in common than the two realize.

At the same time, Cronenberg doesn’t slim down DeLillo’s simultaneously

sprawling and precisely dense narrative as much as he carves his own

flourishes onto it. A couple of scenes, including Packer’s interest in

bidding on a chapel full of art, and his visit to a night club full of

drug-fueled ravers, are only necessary to establish a uniform pace to

Cronenberg’s narrative. But in that sense, these scenes are just as

essential as the ones where Kinski and Torval give Packer advice.

Everything matters in Cronenberg’s "Cosmopolis," but not everything is

necessarily the same as DeLillo’s book. And that makes the film, as a

series of discussions about inter-related money-minded contradictions,

insanely rich and maddeningly complex. We can’t wait to rewatch it. [A]

Credit The Playlist / Via @ThinkingofRob

Via PattyStewBoneCT

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar